Dear Writers (and anyone willing to listen) — #8

Homebound Letter 8 – April 7, 2020

Dear Writers (and anyone willing to listen):

When it comes to books, I’ve never been a big believer in happy endings. But I do believe in hopeful endings. This distinction has guided every story I’ve ever told. And every talk I’ve ever given. And every essay I’ve ever written. Happy endings just don’t strike me as true. But hopeless endings don’t either. Even when a character or setting is drowning in despair, there still has to be hope in order for a story to work. The writers I most admire don’t simply reflect the world, they attempt to transform it in some way. At least that’s the way I’ve viewed things up until now.

But today I want to chuck all that into the Pacific.

Today, a few weeks into America’s version of this global pandemic, all of us stuck in our homes, stuck to our Zoom screens, stuck inside a news cycle that gets bleaker by the day – as we anxiously track this battle with an invisible enemy through social-media-shared infection charts and casualty graphs and unemployment reports, wondering about the wreckage that waits for us on the other side (if we’re lucky enough to make it to the other side) – my old understanding of writerly hope just doesn’t fit the same. It seems outdated. A tiny bit naïve. The nicest dry-cleaned shirt hanging in the closet when there’s no longer occasion for nice shirts.

I don’t know.

Maybe I’m a little lost.

Some background. My name is Matt de la Peña, and I write books. Usually I’m out on the road, visiting schools. Or I’m working on a new project. Like so many of us are working on new projects. But right now I’m staying at home with my family. Because we’re all staying home. I’ve been writing letters to young people, who are attempting to learn from their kitchen tables now, but some days – like today – I feel like writing to writers. To artists and musicians. To anyone who makes things in their free time or is simply willing to listen. This letter is for you.

How do you make a thing you hope might lift someone up while you’re pinned to the ground? How do you build a story that’s full of life while you’re frozen with fear and anxiety?

I’m no rookie when it comes to ordinary sadness. Most of us aren’t. “Sometimes the whole world can seem like a misplayed note,” reads a line from a picture book I wrote called Miguel and the Grand Harmony (illustrated by Ana Ramirez). This is true in the best of times. But usually we’re all so busy we can turn our backs on it, at least temporarily. Ambition can double as a defense mechanism.

A personal theory (one that none of my friends agree with). . . . I believe we’re shaped by a kind of emotional gravity, this invisible force that perpetually pulls us all down to a natural emotional resting place of melancholy. (I’m not talking about clinical depression, obviously. That is something different. That is something I know nothing about.) The way I see it, most of us get moments of genuine laughter. Of rollercoaster thrills. Of intense happiness and pleasure. But these moments eventually burn off. The ride comes to an end. The park employee is there to open the door to our rollercoaster car and usher us out. And it’s melancholy that waits for our feet to hit the pavement.

I’m most aware of this when I’m on the road, away from my family. On the road there are legit visceral lows. Sometimes the tremendous kind. On the road you find yourself ordering a double bourbon at an empty Courtyard Marriott bar in Olney, Illinois, then taking it up to your sad little room to watch CNN on your sad little TV. On the road you find yourself steering a bright red rental car through a McDonald’s drive-through in Wabash, Indiana – and when you pull into the dark, empty parking lot nearby, to guiltily wolf down your quarter pounder meal, you discover that you’re in a cemetery, surrounded by row upon row of mismatched headstones. And worse yet, the whole scene feels startlingly appropriate. (What’s the fancy literary term for that? Objective correlative?)

But even during these road lows, there are secret little rays of light. One day you’ll write about this, you tell yourself. One day you’ll launch into your cemetery story while at a conference happy hour, surrounded by writers and teacher friends. And besides, soon as your event ends you get to go home. The plane ticket is already booked. Look, the printed-out itinerary is right here, folded up in your backpack!

But there are no rays of light when it comes to Covid-19. Not that I can see.

I started this stay-at-home stretch in a good mental space. All right, I told myself. Let’s face this thing head on. Let’s flatten this damn curve. We’ll hunker down as a fam and figure out this ST Math app. I’ll get writing done before the kids get up in the morning. And after they go to bed. But as time has passed, I’ve become increasingly worried about the future. And I’ve been unable to find a path into any of my stories that seems true. Not in this context.

Each night I collapse into bed, exhausted, only to lay awake, cycling through all the regrets I’ve accumulated during the day. I should have worked harder on the new book, which is already past deadline. I should have spent more time with my daughter on her reading and writing. I should have been more patient with my two-year-old son. I should have checked in on my students and researched ways to salvage our podcast. I should have called my folks. My friends. I should have spent less time glued to my phone, scouring the latest news, while my kids tried to get my attention. I should have communicated better with my wife about how we’re both feeling.

All these personal should-haves, while people all around the world are getting sick and dying. While the healthy are losing their jobs. While kids without internet access are falling behind. Or they’re stuck in homes that aren’t safe.

And the worst of it, the experts keep telling us, is yet to come.

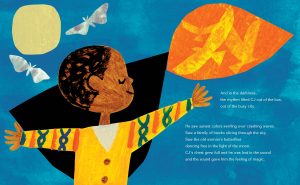

In another picture book I wrote called Last Stop on Market Street (illustrated by Christian Robinson), a young boy named CJ is focused on what he doesn’t have while he and his grandma ride the bus through their city. When two boys climb aboard listening to music on headphones, CJ mutters under his breath, “Sure wish I had one of those.” His wise grandma motions toward a man tuning a guitar and says, “What for? You got the real live thing sitting across from you. Why don’t you ask the man if he’ll play us a song.” CJ doesn’t have to ask, though, because the man is just beginning to play. The blind man sitting beside CJ tells him with a smirk, “To feel the magic of music, I like to close my eyes.” CJ takes his advice. He closes his eyes and listens.

“And in the darkness, the rhythm lifted CJ out of the bus, out of the busy city. He saw sunset colors swirling over crashing waves. Saw a family of hawks slicing through the sky. Saw the old woman’s butterflies dancing free in the light of the moon. CJ’s chest grew full and he was lost in the sound, and the sound gave him the feeling of magic.”

I’ve read this book and these lines countless times over the past several years – in elementary schools and middle schools and high schools, at bookstores and book festivals, at professional development conferences – and every once in a while the simple words take on greater meaning because of something that has preceded my appearance. I once read the book to a class of misplaced elementary school kids in Houston just weeks after Hurricane Harvey. I once read the book to a room full of incarcerated mothers in a Minneapolis detention facility, and then sat with them and a guard as they recorded themselves reading the book for the child or children they were separated from. I once read the book to a group of Brooklyn children who were part of an afterschool program for homeless youth. I once read the book to a group of undocumented 6th graders in Denver who were terrified by recent ICE raids in their city. The darkness was different in each of these settings. But the need to somehow rise above it was the same.

Earlier in my career I mistakenly believed I was (at least partially) responsible for bringing the rhythm and magic to all the communities I visited. But I was wrong. Turns out it’s the audience members themselves who possess the magic, who are capable of healing. It’s true, sometimes they might use my book as a tool. Or even my appearance. But it could just as easily be another book or another author. And isn’t this the greatest testimony for the power of literature? That while no single book is magical on its own, stories of all kinds can help unlock the magic in a reader or readers.

A couple days ago my son was super upset when he woke up from his nap. I hurried into his room and scooped him out of his crib and carried him over to his glider chair where I rocked him for several minutes. He leaned his face against my chest and slowly but surely he calmed down. My writing had gone nowhere that morning, but at least I was able to soothe my son. I remember feeling so good about this. I remember feeling like I had purpose. But then something surprising happened. He put his little hand on top of mine, and he began slowly and softly rubbing the back of my finger. Over and over. And it made me so happy I started to tear up. Because I realized he was soothing me, too. Somehow his 23-month-old brain understood that his dad was stuck in the darkness, and he was trying to lift me out.

And as we rocked together in his room, my thoughts drifted to all the events I’ve had cancelled for spring and summer. And I anticipate more of the same come fall and winter. It dawned on me what I miss so much about speaking at schools or reading at bookstores. It’s the same thing I was getting from my son. Though I step into these presentations ready to give myself to an audience, so often I’m the one filled with gratitude after I’ve finished. Because here’s this group of young kids listening to my stories. Here’s this too-cool-for-school high school kid raising his hand at the end of my talk and asking me an earnest question about reading. Here’s this group of hard-working teachers clapping for me as I fold up my laptop and leave the stage. I can’t explain how gratifying this is, to know that a group of people is listening to my words, uncovering my sagging heart with their eyes and ears.

Near the end of my all-time favorite novel, Suttree, by Cormac McCarthy, the main character Suttree, in a state of spiritual contemplation, has the following conversation with his own shadow:

“What do you believe?”

“I believe that the last and the first suffer equally. Pari passu.”

“Equally?”

“It is not alone in the dark of death that all souls are one soul.”

Pari Passu. I’ve always been drawn to this idea. Especially now, when so many of us are truly suffering. But maybe it’s helpful to know that we’re suffering together. That all souls are one soul – even when we’re at least six feet apart.

I used to believe my strength was in my silence. In my ability to bury any sadness and keep pushing ahead with the same ol’ detached expression. But I’m older now. And I’ve been humbled a time or two. Being strong, I’m beginning to understand, is the ability to reach out to others, to share how you feel. Which is why I flipped on the overhead light that day I was rocking my son after his nap. So he could see the tears on my face. So he could know that it’s okay to feel things.

Thank you for taking the time to listen to me during this strange time in our lives. I’d like to be able to listen to you in return. Please leave me a note somewhere, or email me at: hellomattdelapena@gmail.com.

Matt